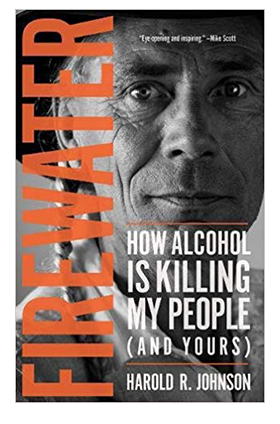

Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing my People (and Yours) by Harold R. Johnson | University of Regina Press, 2016

Book review by Christopher Malnyk, IPAC Saskatchewan Communications Chair.

Over the last several years, the University of Regina Press has published a number of books dealing with the history of and current challenges facing Indigenous Peoples. From Clearing the Plains to The Education of Augie Merasty to Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing my People (and Yours), U of R Press has brought forth three national bestsellers that present stories of both abject horror and ultimate hope for the future. In honour of 2017: IPAC’s National Year of Dialogue, we are presenting reviews of these important works.

Released in 2016, Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing my People (and Yours) is Harold Johnson’s testimony to a problem he passionately and in a deeply personal way argues has taken and is taking a devastating toll on the lives and communities of Indigenous Peoples across Canada. Johnson writes from the perspective of a Cree Crown Prosecutor working in Northern Saskatchewan with direct experience of the problem. The book is a direct and clearly heartfelt plea for Indigenous People (and indeed all Canadians) to take a deep and serious look at the role of alcohol in their lives. The book also asks for a re-examination and re-definition of the stories that have been told (and are being told) that continue to create beliefs that no longer serve a healthy purpose in the lives of Indigenous Peoples.

“This small book is a conversation between myself and my relatives, the Woodland Cree. Its purpose is to begin a discussion about the harmful impacts of alcohol consumption and to address the extreme death rate directly connected to the use of alcohol in our Northern Saskatchewan communities.”

Harold R. Johnson

I must state for the record that I am not an Indigenous Person; indeed, I am kiciwamanawak. This is the first book in which I have encountered this Cree term for Non-Indigenous People. Firewater is full of Cree vocabulary like this along with traditional narratives that Harold Johnson utilizes to illustrate how powerful stories can be in defining both a people and an individual. This use of Cree terminology and traditional stories is a key element of Firewater that made the book such a powerful read for me.

As I was reading, it was never far from my consciousness that I was consuming this book as kiciwamanawak and that I would have to take great care to try and suspend some of the ingrained stories that I hold dear that have shaped my own beliefs and with which I live my life. In the end, I discovered some new facts not only about an important issue for the future of Saskatchewan but also something about myself – something about stories and the power they have over our destinies. Although I am kiciwamanawak, the book became deeply personal to me in a way that I could not have imagined when I first picked it up. Indeed, I have read and internalized Harold Johnson’s words and I believe that they are tremendously helpful. I hope to use them in a good way.

“I speak, however, only to my people, the Woodland Cree. I have no right to speak to anyone else. But if you hear my words and if these words help you, then take them and use them in a good way. If you cannot use them in a good way, then leave them here.”

Harold R. Johnson

I could go on and restate the facts outlined in the book (as many other reviewers have) regarding how alcohol and its use is causing dire problems in the lives of Indigenous (and also Non-Indigenous) Peoples across Saskatchewan and Canada. I could quote the statistics regarding accidents, violence, and death that Harold Johnson provides. But those cold, hard facts are only the foundation of the book and a way to scope and size the problem. What I think is much more important about Firewater is the argument that weaves its way throughout that stories and the way that they have been adopted and have formed a set of beliefs about alcohol is the core problem that needs to be addressed. Johnson presents the case that these stories and the beliefs that they perpetuate are the real root of the problem and that Indigenous Peoples need to take back control of their stories in order to find a better, healthier way forward. This strikes me as a very compelling argument for all people whose lives are being negatively impacted by alcohol (or any other negative influence for that matter). We all need to become mindful of and take back control of the stories that we believe and hold dear.

“We can live any story that we want. We can live a romance, or a tragedy, or a comedy, or a mystery, or a fantasy, or a fable, or a fairytale. We can decide which story we want to be in and tell it to ourselves. The only limit on our ability to choose our own story is the story into which we are born. We have all been raised in a particular story. When we recognize it as story, it loses its power. This is especially true of victim stories. All of what we refer to as ‘society’ is the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves.”

Harold R. Johnson

There is a message here for all people – what stories are we living out in our lives? Do they serve a healthy and uplifting purpose? Even if we believe that we are living out healthy stories, are we actually living consistently with them? For example, Harold Johnson cites the behaviour of legal teams that fly into Northern Saskatchewan to deal with alcohol-related problems, subsequently putting people in jail, and then getting back on a plane loaded with booze for their trip back home. As a result, there is also a message here for all kiciwamanawak public servants who are tasked with attempting to deal with and help contribute solutions to the problems that are facing Indigenous Peoples – deeply consider the stories that we are living by and whether or not they are also part of the problem.

Listen to an interview with Harold R. Johnson on his book Firewater from CBC Radio’s “The Next Chapter”.